This is an essay that is long overdue. It’s been well more than a year since I ate delicious food paired with fantastic wines at Pheasants Tears tasting room in Sighnaghi, Georgia. The dishes and the wine were wonderful and remain vivid in my memory, but they were also matched by the hospitality shown to me by the people of Pheasants Tears. My apologies, Gia, Tamar, Alex, and all of the other great folks I met that day. I hope that this post expresses how grateful I am for the time we spent together.

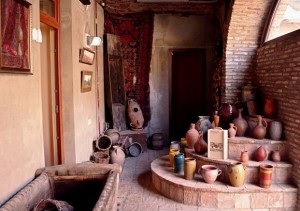

From the moment one steps through the elaborately carved doors of Pheasants Tears, you know that this isn’t just another tasting. You can feel the difference in the dusky pink stones and bricks that line the walls of the tasting room and you can see it in the smiling and laughing faces of the guests. There is LOVE here. You are surrounded by people who love what they do and who are anxious to share it with you.

Visits usually begin with a tour of the tasting room and its modest winemaking museum. A centuries-old carved, wooden basin for holding grapes for processing hints at old the art of vintning is in Georgia’s eastern Khaketi province. Sighnaghi is a few hundred miles from Areni-1 cave with its Copper-Age wine production site (dated 4223 – 3790 BCE). In between these two points lies Shulaveri, Georgia where the oldest domesticated grape pips have been dated to eight-thousand years ago. So clearly, viticulture, vintning, and wine drinking in Georgia are amongst the most ancient in the world.

Traditional Georgian winemaking is done underground. Large earthenware vessels called qvevri are coated with beeswax to make them less porous and to provide a near neutral pH surface for the wine to ferment in. The qvevri are then sunk into the ground or buried below a cellar in a wine-making facility, and usually left to season or age before first use. Then, the qvevri are filled with partially smashed grapes and their accompanying liquid, and pounded some more to fully macerate the grapes. The contents of the qvevri are stirred several times a day to push the skins of the grapes down into the wine The only yeasts used to ferment the grapes are the natural yeasts that come in on the grapes. After a week or two of stirring, the qvevri are sealed with stone caps and clay for months or years as the wines mature.

I was lucky enough to be greeted and toured around by the brilliant man who makes the food at Pheasant’s Tears tasting room as unique and as unforgettable as its wines – Chef Gia Rokashvili. His culinary creations meld the freshest Georgian herbs and produce with modern, healthy, preparation methods and deep knowledge of both traditional Georgian and French cuisine. He calls this his, “fusion,” style. I call it inspired and delicious.

A large party of Russian tourists were in mid-meal when I arrived, so after my tour, Gia gave me into the care of his wife, Tamar who is the maître d’hôtel and manager of the tasting room and a visiting American vintner named Alex Rodzianko. As Gia went to oversee the kitchen, Alex and I began tasting – and eating.

We started with a light white Chinuri – a great summer wine – with a floral aroma and a crisp finish, and moved on to an amber Rkatsiteli (my husband’s favorite), another light wine with a surprisingly full body given its color and aroma. As we tasted, a parade of light dishes began to flow from Gia’s kitchen to our table. A salad of tomatoes and cucumbers was first up, followed by some heavenly roasted eggplant with garlic, walnuts, and herbs. Last up was a Georgian specialty called jonjoli which is a seed pod of a bladdernut (Staphylea colchica) that tastes something like a caper, only Georgian’s prepare them with the tender, young greens attached. Lightly tossed in safflower oil and a bit of seasoning, its not to be missed.

After the Rkatsiteli, Alex offered me a delicious Tavkveri, a full bodied red with hints of cranberry and hibiscus. It has an incredible floral aroma that fills the senses and hints of the wonderful flavors to come. We closed with a glass of chacha to aid or digestion. Chacha is technically a grape brandy, but it is very strong (like grappa on steroids). It is a traditional homebrewed liquor that can also be made from other fruits such as figs, mulberries, and tangerines, that is now being made by professional distillers. The one I sampled that day is produced by Pheasant’s Tears. By the time we got to the chacha, my driver walked into the tasting room for the third time and began glowering at me with a smokiness that only a Georgian can muster. He also had his ample arms crossed across his chest. Subtle though he was, I got the message. Reluctantly, I had to leave. Thank yous and hugs all ’round and a few bottles to bring home and I was on my way.

If your own travels take you to Georgia, do pay a visit to the Pheasants Tears tasting room. It is a wonderful place with great wine, delicious food, and wonderful people. A great place to spend a day, or two, or three, and feel the love that they bring to their work. In the car ride back to the city, I began to understand why people return again and again, and some, never leave.

(Words and all photos by Laura Kelley)