From cowrie shells; and iron, copper and silver coins; to various kinds of paper, many different materials have been used by merchants and customers as credit or legal tender. Bolts of silk measuring roughly 22 inches wide and 41 feet long were also used as a form of currency by the Chinese, especially in foreign trade or as gifts to foreign lands. The silk used as currency was of lower quality than that used for luxury goods or tribute. Generally it was a plain basketweave (one thread above, one below) and both undyed and undecorated, as in this photograph of a silk bolt used as payment for the expenses of soldiers at a garrison in Loulan (Korla) in the 3rd or 4th Century ACE.

It wasn’t until the 20th Century, that people actually began to print money on small pieces of silk and use them as banknotes. This use of silk money was usually a temporary thing, fueled by a local or regional government’s need to raise money quickly, or by a shortage in paper, or both.

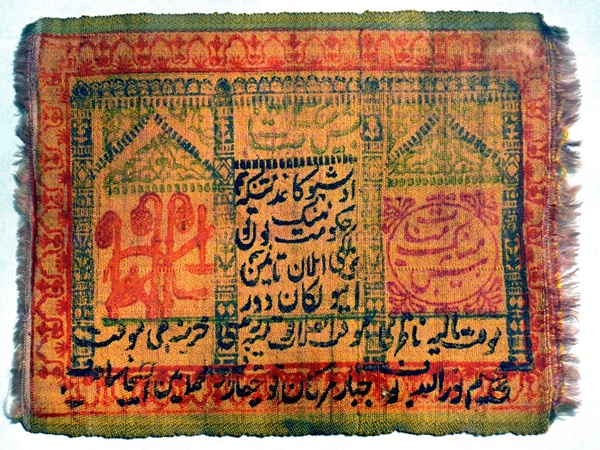

In 1918, Khorezm (now in far western Uzbekistan) was seized by Junaeed Kurban Mamed when he invaded Khiva. Mamed executed the legitimate ruler Asfandiyar, set Asfandiyar’s younger brother, Seyeed Abdulla, up to rule in his place. This invasion and coup threw the economy of the state into chaos, and the new government started printing banknotes to raise money. Lacking sufficient paper resources, they started to print and circulate currency on small pieces of silk.

Unlike the presses used to print paper money, the designs and official seals on the silk currency were applied by hand with wooden (probably elm) stamps, with separate stamps used for each color. The dyes used were traditional and derived from local plants and fruits with oak-apple (dark brown to black), pistachio leaves (green), madder root (red), and the Japanese pagoda tree flowers (cream to yellow).

The notes were printed with Arabic, Uzbek, and Russian text. The notes were issued in 200, 250, 500, 1000, and 2500 tanga denominations. At the time of issue, the value of 5 tanga was approximately equal to one Russian ruble, so the 250 tanga note was valued at 50 Russian rubles.

April 1920, on the territory of the Khiva khanate the Khorezm People’s Soviet Republic (KPSR) was established, and more silk money was printed. In 1923 an even exchange of the silk banknotes and soviet currency was established. Despite this, many people held on to the silk banknotes and up until the 1950s and 1960s homemade quilts and suzani in the Khiva region could be found incorporating the banknotes as part of the design.

A little Silk Road History for a warm January day. . .

(Words by Laura Kelley. Photo of Silk Currency Bolts from the British Museum (Collection Image AN00009/AN00009325_002_l.jpg); Photo of Silk Money, Khorezm, UZ by Laura Kelley.)

Did China print their notes on linen in 1933?

Hi Julie:

I don’t know. I have never heard that they printed money on silk at that time. I do know they minted coins in a wide variety of metals when they abandoned the silver standard because of the high price of silver.

I wonder why silk was the chosen form of currency. I guess it was easier to access over the precious metals.