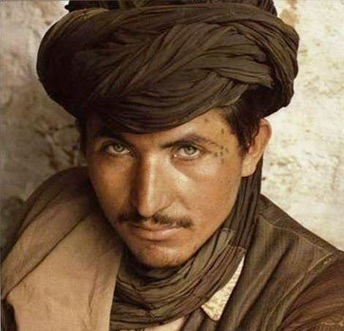

The effect of all of this blending of cultures on Afghan cuisine has produced a merger of both western Asian, which is still heavily influenced by European food and the cuisines of the Levant states, with southern Asian cooking or cuisines of the Indian subcontinent. From the West, we still see a wide variety of familiar spices— fennel, bay leaf, mint, and saffron—but these are often used in concert with southern and eastern Asian spices such as cardamom, cinnamon, or ginger rather than as main flavors.

Once again the Persian influence is strongly felt in the combination of fresh and dried fruits with meat dishes, in the use of sour grapes as a “souring agent” in a wide variety of foods, and in sumac as a spicy garnish to sauces and skewered meats. Another much-generalized trend that Afghan food has in common with southern and eastern Asian cuisines is the eating of smaller portions of animal protein at most meals. Kebabs may seem like a lot of meat, but most of this is in fact in the presentation instead of on the portion scale. Part of this trend away from meat has to do with the cost of meat, but part of this is also due to simple cultural preference.

The recipes offered in the Silk Road Gourmet give a good overview of the complex flavors that prevail in Afghan cuisine. In meats, they range from the gentle Afghan Chicken Kebab and Lamb Chops Afghan Style with dashes of cinnamon and black pepper working with the flavors of the meats to slightly accent them, to the sharp Lamb with Lemons and Pine Nuts with its spicy trio of cardamom, coriander, and cinnamon adding their pungent flavors to a lemon-pepper sauce. The vegetable recipes offered are not shy cousins to their meaty relatives; in fact, some of them—most notably, Tamarind- Ginger Potatoes and Spicy Eggplant with Mint—may be even more spicy than most of the meat dishes. Afghan vegetable dishes aren’t just about bold flavors, though; sometimes they gently coax diners into submission, as with Sautéed Quinces, where nutmeg and cinnamon work in concert with basil to bring a unique flavor to a fruit that is much underappreciated in the West, or Sweet and Spicy Squash where a sweet, baked butternut squash absorbs a sweet and spicy tomato sauce seasoned with ginger and garlic to magnificent results.

If you are curious about Afghan food – perhaps having dined in Afghan restaurants a few times – I suggest you check out the Silk Road Gourmet to try some of this delicious food at home. You will instantly recognize some of the flavor combinations from the Persian/Iranian portfolio, but other tastes will be brand new and closer to those of Indian subcontinental cuisines. (Words by Laura Kelley, photo of An Afghan Man from the U of Colorado at Boulder website and photo of Kebabs from the Afghan Embassy website)