The University of Pennsylvania Museum displays artifacts

from Caucasian travelers on the Silk Road.

In a desolate, eastern world of salt and sand, where blinding windstorms were common and potable water was rare, the mummified remains of people from the west have been found. Why they died, where they came from and where they were traveling to is unclear, but for a short time, they were put on display in the United States – another Silk Road exhibit that I just couldn’t miss.

A couple of weekends ago, we bundled the kids into the car and drove to Philadelphia to see the exhibit, Secrets of the Silk Road, a collection of artifacts from Silk Road travelers that spans more than 2,500 years of the region’s history. One of the oldest objects on display was a female mummy with Caucasian features and long auburn hair dated to almost 2,000 years BCE. Dubbed the, ‘Beauty of Xiaohe’ she slumbered silently in her glass case dressed in plain, pale wool and cotton clothing and a felt hat with a few personal artifacts from her gravesite.

Despite false claims that Silk Road trade began with Alexander or with the Romans, episodic trade between east and west – between China and Afghanistan or the Indus Valley – began around this time. Some of the first items to be traded were the semi-precious lapis lazuli from the west for all shades of Chinese jade. The Beauty of Xiaohe and her fellow travelers could well have been on an early trade mission to exchange precious goods such as these, make a buck, and open the doors of cultural exchange that became the Silk Road.

Conjecture, yes, but these travelers could also been engaged in trade for early Chinese silk which was perfected around this time in the Yangtze’s late Longshan culture. Or, they could have been in search of domesticated horses and pigs which the Qinghai’s Qijia culture excelled in. They also could have been part of the Aryan migrations which began in earnest around this time as well.

Whatever goods, economic or living opportunities brought Caucasians into far eastern Central Asia and Western China, they kept on coming – despite the hardships of the Tarim – which took many lives. Also on display, was the mummy of an infant from about 1000 BCE. The baby was buried, swaddled in red woolen shawl with an azure blue bonnet covering its head. Stones covered the dead child’s eyes and next to it lay a tiny drinking horn and sheep udder – presumably so it could feed in the afterlife – another casualty of the Silk Road.

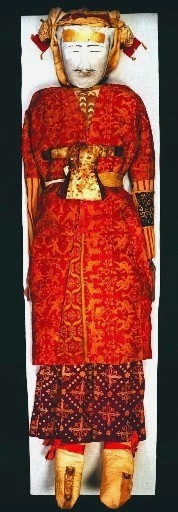

A later set of clothing from the 4th or 5th Century CE spoke volumes for the wealth to be had on the early Silk Road. The mummy of Yingpan Man was deemed too fragile to tour, but the Chinese Government generously sent his clothes. He must have been truly magnificent: A tall man from Samarkand – over six-feet – in a gorgeous, red belted caftan with a small army of little golden Greco-Roman putti and bulls or goats woven in gold brocade. His trousers were deep purple with gold brocade in scroll and cloud-like designs. The caftan is believed to have been woven in the Eastern Roman Empire and traded East. The trousers – or at least the fabric they were made from – may have been Levantine as well because of the distinct purple color – a shellfish derived color the Phoenicians were renowned for.

Of course I wondered what these early Silk Road travelers and traders ate, and this time, I was not disappointed. Grave goods are a fantastic source of information about what people ate, and form the backbone of what we know about the diets of several ancient cultures, including the Ancient Egyptians. But with so little known about the Tarim travelers, the elaborate food items found with them are a revelation! There are cookies and biscuits modeled after plum blossom and chrysanthemums, there are wontons and spring rolls and several other types of snacks to be had on the long journey to either Xian or the afterlife.

For me the exhibit wasn’t about naturally-preserved corpses (I’ve seen a lot of corpses in my day – too many really), but it was about the birth and blossoming of the Silk Road. Goods and gold, of course, but more importantly, the Silk Road was about the flow of ideas and cultures that became and engine of change in the ancient world. Every step that the Beauty of Xiaohe or Yingpan Man took has influenced the world we live in today and will continue to echo long after we are gone. I wonder if our own lives will have such impact on the future? (Words by Laura Kelley, Photos from the Secrets of the Silk Road exhibit from Museum sites.)