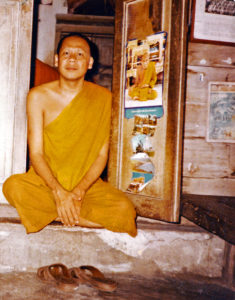

I was usually still sleeping upstairs when the monks came round to beg for their food every day. But sometimes, I got up before dawn, stepped out of the netting that protected me at night from falling reptiles and made the offering myself. I spent several months in Thailand, in a small village near Haddyai, Songkla with no running water, electricity or telephone. Happily off the grid, I learned a great deal about Thai language, customs and culture, spent some time as a Buddhist nun, chewed bitter betel, and learned how to batik really well. I also learned a lot about Thai home cooking.

Thai food has become very popular in the west, but I’ve found, much to my disappointment, that few of my favorite dishes are ever offered on the menu. Where is the pat sataw? Where is the curried fish for breakfast? And where are the sweet treats made of sticky rice and sliced fruit that are tied up in bananaleaf packages? Also missing is the freshness of the meal ingredients: rice from the fields behind the house, fish from the river, and sataw beans from the tree next to the house. In my mind, I can still see one of the sarong-clad local men running up a coconut palm to knock a few of the barely ripened seeds to the ground for the women to cook with. He crashes a machete through the green shell and sips the fresh coconut juice inside before he hands me the other half. I bring the coconut-cup to my lips and take a little sip of heaven.

Since the Thai peninsula played an important part of maritime and land trade on the Silk Road, southern Thai cooking has Indonesian and Indian elements in it that are often lacking in the regional cuisines of the rest of the kingdom. The copious use of tamarind, lime and strong rice vinegar as souring agents are a couple of these elements as is the enjoyment of skewered and roasted meats with peanut sauce. the use of sataw are shared with the Indonesians and Malaysians who use them as part of some sambal preparations. The Thais (and the Malays on the peninsula), however have put them centerstage in a spicy, garlic laden stir-fry made with or without the addition of meat or fish. Occasionally, the Thais have even imported entire dishes and put a Thai twist on them that made them uniquely their own. This is most evident in their mussuman curry with cardamom and cinnamon and chicken with basil with India’s spicy, holy basil. Thai cuisine also has lots of Chinese elements, such as enjoyment of noodle-based dishes, stir frying, and the use of light and dark soy sauces – but these are not limited only to the south.

During my sojourn in Thailand, I also spent some time on Phuket and Phang Na before they had been developed as resort destinations. Of course there were a few bungalows for rent – but these were occupied mostly by vacationing Thais. For the most part, the west had yet to discover these islands and they were still unspoiled tropical paradises. Completely absent was the “desire and the carrot and the carrot and desire. . .” of western living as stated beautifully by the late, great Spaulding Gray in his masterpiece, Swimming to Cambodia. At that time, there was little to do there except relax in freeform or study at one of the local monasteries. For every eden, however, there is always a Lilith or a snake, and the waters around these islands were prowled by sharks which often came into the shallows and in some places there were incredibly strong rip tides that could transport swimmers far out to sea. Islanders often spoke about the predatory seas and tallying the ocean-caused injuries and deaths was something of a local hobby. In microcosm, the sea held captive the danger that was absent on land, sort of like the sea monsters that often lurk just offshore on antique maps.

I remember one evening I stood by the edge of the sea and allowed it to nearly bury me in the sand. With each rhythmic stroke of the waves I sank deeper into the sand. First my toes, then my feet and then my ankles were devoured in turn as I watched the sun set. As the sky darkened, the waves began to lap at my knees and my self-preservation instinct belatedly kicked in. Even though I had decided to free myself, the ocean was wont to let me go and I had to struggle to get out of the premature watery grave that the waves had dug for me. My Phuket was a strange land filled with wonders and demons alike.

Only a handful of years after I returned, I saw a cashier at a Chinese noodle shop in the upper east side of Manhattan with a Club Med Phuket t-shirt. I froze, unable to move or speak as I stared at her shirt, remembering the island, the monks and the brief life I had known there. Eventually, I stammered something incomprehensible, paid for my noodles and stumbled back to my office, more or less having lost my appetite.

Even though my trip took place many years ago, there was a great deal of political unrest at the time in the south that took the form of killings, bombings and general Muslim-Buddhist tension. I read with interest a recent post over at the Rambling Spoon which attests that the situation has changed little in the intervening years – except that it may have gotten worse. At issue – then as now – is the desire by some for the secession of the southern three provinces from the kingdom of Thailand. For me, however, the violence of the cities, rarely spilled over into the countryside and that’s where I spent most of my time, so it hardly impacted my consciousness at all.

On the whole, the time I spent in Thailand was a transformational experience. It reset my life-clock and gave me a view of the world that only solitude and study far away from the hustle and bustle of a city can do. I still think of the troop of little children who followed me around everywhere I went, and I still hear the chorus of little girls studying traditional dance who stretched their fingers backwards and held them to the count of ten: nung, sung, sam, see, ha, hok, yet, pet, cau, sib. I miss the midnight songs and the clattering on the tin roofs of the big, bruiser cats that were twice the size of the tawny, emaciated felines we call Siamese in the west. And yes of course, I miss my favorite dish – the pat sataw. (Words © Laura Kelley; Photograph of the Monk at the Monastery by Laura Kelley; Photograph of Phuket Sunset © Mikhail Nekrasov| Dreamstime.com)