Although not specifically promoted by the National Restaurant Association as a top food craze this year, umami is generating a lot of buzz on the street as a trend to expect more of in 2014. In part, these expectations are due to the continued expansion of the Umami Burger restaurant chain, but it is also because the umami content of produce and prepared foods and snacks is increasingly a selling point in the mass-consumer market. In short, we are becoming more umami aware, and consciously seeking out savory foods rich in umami.

Sort of like a sixth sense, umami is the fifth taste that represents savoriness. Like me, you may remember learning about the four tastes we inherited from the ancient Greeks: sweet, salty, sour and bitter. I vividly recall mapping these tastes on different areas of the tongue with a cotton swab in elementary school. A combination of modern science and culinary explorations into how we taste food, however, has turned this notion on its head and added umami to our pantheon of tastes.

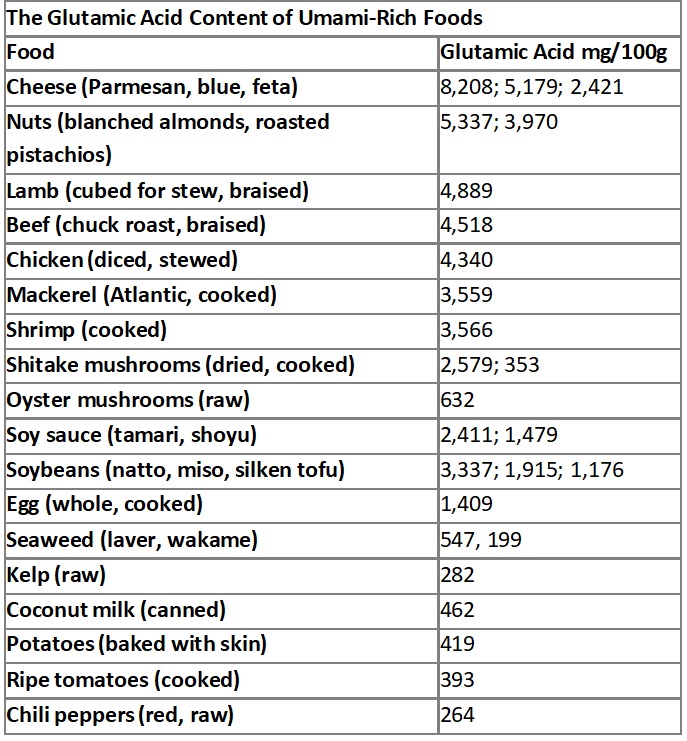

Umami is carried in a number of molecules, but most notably in glutamic acid. Many foods are rich in glutamic acid, including ripe tomatoes, some mushrooms, asparagus, seafood, seaweed, kelp, soy sauce and some cheeses. Tasteless on its own, it is only when glutamic acid is broken down into L-glutamate by cooking, fermentation or other processes such as ripening in the sun that it offers up its savory taste.

Discovered in 1866 by German chemist Karl Heinrich Ritthausen, glutamic acid was later identified in evaporated kombu (kelp) broth in 1908 by Japanese researcher Kikunae Ikeda of Tokyo Imperial University. When he tasted the crystals in the evaporated broth, Ikeda found that they had an undeniable savory flavor that he detected in many foods. He named this “pleasant savory taste,” umami or うま味 from a combination of umai (うまい) “delicious” and mi (味) “taste” in Japanese.

Around the same time that Ikeda was investigating the science of taste, renowned French chef Auguste Escoffier was developing recipes rich in umami flavor using his intuition and culinary skill to explore the sensory qualities of food. One of the secrets to his deft use of umami was the importance of stock (particularly veal stock). He deglazed seared roasts with it, made soups with it, and used gelled stock in a wide variety of other dishes to add savory flavor to them.

What Escoffier didn’t realize was that his use of stock to add umami to French dishes was similar to the use of dashi in Japanese cooking. Dashi is a stock made from umami-rich fish (anchovies or sardines) or fish flakes (bonito) often in combination with different kinds of kelp and a small amount of sake. The best dashi is made by allowing ingredients to soak overnight before straining to extract and concentrate the glutamic acid in the stock.

So, many classic French recipes are ready sources of umami, as are a wide variety of Japanese dishes. Where else can you find umami-rich combinations? Well, dishes made with tomatoes and cheeses are like umami bombs that are enjoyed all over the world. In the Mediterranean, the most familiar sources are Italian dishes made with marinara sauce and Parmesan cheese. In Asia, the Tibetans enjoy the combination in their tomato-laden lamb or beef curries that use the blue cheese churu, and in the cheese-filled momo dumplings accented with a spicy tomato sauce dip.

Elsewhere along the Silk Road, salads mixing tomatoes and cheeses abound from western Asia through the Himalayas and into western China. One of my favorites is from Turkmenistan that uses cider vinegar and a little salt to accent the tomatoes and cheese flavored with cilantro. Another is one from Bhutan that uses the crackle of Szechuan peppercorns to blend pungent yak’s milk cheese with tart tree tomatoes. Both salads are loaded with glutamic acid and have high umami factors.

Other Silk Road dishes that have umami appeal are Persian omelets, called kukus, which are enjoyed all around western Asia. Turnovers stuffed with lamb and cheese with herbs, often called samosas, are enjoyed from western Asia to western China and are a great source of umami. I had the samosas pictured here at the bazaar in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, last year. Along with a salad of tomatoes and cheese, and a small kebab, it was a perfect lunch and in a way, indescribably savory and delicious.

(Words and photo of Umami Uzbek Samosas by Laura Kelley. Data for table from USDA SR-21.)

(Originally published in Zester Daily.)